Unless you are registered in some outpost with only about half a dozen names on the roll, you don't know what it is like to see a public official recalled.

The largest Louisiana burg to recall an errant politician in recent years was Port Allen, home to fewer than 5,000 souls, where Mayor Deedy Slaughter was so impressed with her own performance that she awarded herself a $20,000 raise without city council approval. For that and other unsanctioned raids on the public purse, voters gave Slaughter the early heave-ho in 2014.

Prising a politician's snout from the public trough by recall is not feasible in a larger political subdivision, however. Gathering enough signatures is just too big an ask. Take, for instance, another Louisiana politician who pocketed an illicit raise and altogether lived high on the hog at public expense, former St. Tammany Parish coroner Peter Galvan.

The law eventually caught up with Galvan, who went to prison in 2014 — evidently a bad year for light-fingered elected officials — but he proved immune to recall. It was the same story just the other day when the latest Louisiana politician targeted for recall, New Orleans Mayor LaToya Cantrell, survived comfortably, despite an opposition campaign that was well financed, widely publicized and professionally run.

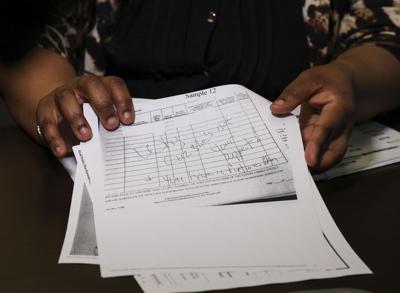

So far as state Rep. Paul Hollis, R–Covington, is concerned, this all proves that the current signature requirement for a recall petition — 20% of a district's registered voters — needs to be reduced. He has a bill pending that would lower the threshold to 20% of the turnout in the most recent election.

The difference could be dramatic. At the start of the campaign to recall Cantrell, organizers needed almost 50,000 signatures to force an election on the sole question of whether she deserved to remain in office. Under Hollis' proposed standard, a mere 15,065 John Hancocks would have sufficed to put Cantrell's political future in jeopardy.

But the present set-up provides a perfect balance. It preserves the reassuring illusion that a mechanism exists to consign an unwanted politician aside mid-term but spares the electorate the tedious chore of yet another trek to the polls.

If a politician is crooked or incompetent enough to threaten the integrity or smooth running of public life, we have ample checks and balances in place. As a last resort, the criminal justice system is poised to mete out retribution and take crooks out of circulation.

Hollis believes recalling a public official should be difficult but not the impossibility it is under the current system. In fact, that system works just fine by letting voters believe they exercise total control without giving them a chance to gum up the works.

It is a cherished American conceit that all politicians are crooked and feckless, so Louisiana would be awash in recall petitions if the signature requirement were significantly reduced. We would be so preoccupied with the question of who should run the state that we'd forget how to do it.

Since the standard term for public office is four years, there'll always be an opportunity just around the corner to vote the bums out anyway. Meanwhile, politicians will identify our needs and promise to bring what is missing in our lives.

Who knew that what we need is more elections?

Email James Gill at gill504nola@gmail.com.