Hundreds of thousands of people are expected to descend on New Orleans over the next two weeks for the city's first large-scale Carnival in almost two years. In the 37 remaining parades, float riders will lob beads to crowds lining the streets, krewes will host huge indoor Mardi Gras season balls and an influx of tourists will spill out from hotels and bars, all in search of the legendary public party.

But after inadvertently launching a superspreader event that seeded coronavirus infections across the South in 2020, city officials and health analysts are approaching this year’s Carnival with caution, even as decreasing COVID-19 numbers are casting an optimistic glow on predictions for the human cost of the gathering. Perhaps more concerning is the shrunken pool of health care and emergency response workers available to handle the many visitors and injuries that always accompany the celebration, officials say.

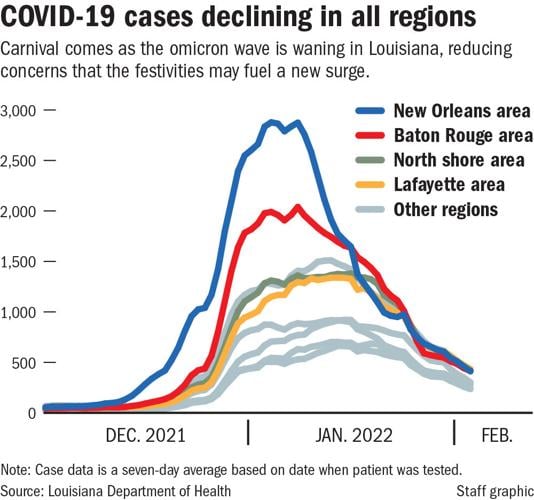

In one sense, Carnival comes at a particularly fortuitous time this year. The omicron variant exploded in New Orleans and then across Louisiana in mid-December, driving infections within a month to their highest rates of the pandemic. But that was followed by an equally quick drop, and Fat Tuesday falls relatively late on the calendar this year, on March 1.

"I think, looking at the numbers, it's very possible we will have come down completely from this surge by Mardi Gras day," said Dr. Joe Kanter, state health officer for the Louisiana Department of Health.

While metrics are still higher than their pre-omicron lows, infections have plummeted 85% since peaking three weeks ago. There are 1,000 fewer people hospitalized with the virus than at the peak of the current wave, and test positivity rates are dropping from the astronomical levels they hit in January to more typical levels.

Louisiana also will have more protection as a result of the recent infections, which will provide short-term defense against a large spike in cases.

New Orleans has instated an indoor mask mandate, and anyone older than 5 must show proof of vaccination or a negative test to access many indoor businesses.

Strain on health care

But in another sense, New Orleans has never approached this busy season with so little reserve in terms of health care delivery and emergency management services.

“It’s not the first time we’ve done this, obviously,” said Susan Hassig, an epidemiologist at Tulane University. “But it’s the first time we’ve done it with such a strained workforce and a depleted workforce of police, fire, EMS and health care. I do think it’s going to be a challenging period.”

Mardi Gras season is a busy time of year for emergency medical services and hospitals even without a pandemic. This year, Emergency Medical Services will rent 10 additional ambulances from out of state and get additional support from the Federal Emergency Management Agency, EMS spokesperson Jonathan Fourcade said. Yet it will be operating with fewer technicians than typical.

“We're still very understaffed,” said Fourcade. “Last I heard, I think we were short about 30 people.”

Waiting on 911 response

Those who call 911 for non-emergency situations can count on a wait. Hospitals are often on "diversion," meaning they don’t have enough staff to take emergency patients, Fourcade said. That means ambulances must constantly rotate where they take patients. If someone needs an ambulance for a non-life-threatening condition in the Central Business District, for example, they might be taken to a hospital 20 minutes away in New Orleans East.

“Just because you call an ambulance does not mean you’re going to get seen quicker,” Fourcade said.

Because of the strain on EMS and hospitals, Fourcade recommended using one of the five first aid stations that city workers will set up near parade routes, or finding a way to an urgent care or emergency room without calling 911 unless it’s a true emergency.

Police shortage trims parades

Due to a lack of police officers, the lengths of parade routes have been shortened. While this supposedly creates a more manageable route for police, it also packs spectators into a smaller area to catch a glimpse of the processions.

Being outdoors is much safer for avoiding a virus spread through close contact, but that benefit is lessened in crowds. In those situations, a mask can help.

Though City Hall has recommended masking on crowded parade routes, analysts are somewhat split on whether that’s necessary. Hassig, who rides with the Krewe of Muses, said she will wear an N95 mask on the float and likely avoid crowds for other parades.

Assessing risk

In general, health specialists recommend assessing personal risk tolerance in combination with the layers of protection - masking, vaccination and a booster shot - to determine one's behavior.

Chad Roy, director of infectious disease aerobiology and biodefense research programs at Tulane University's National Primate Center, said the appropriate levels of protection vary somewhat with how one is celebrating. A crowded bar or restaurant, for example, is "probably a high-risk environment because you have to make the assumption that the virus is still out here in some shape or form," and so masking with an N95 even if vaccinated in an area without a mask mandate is the right approach, Roy said.

On the other hand, a vaccinated person outdoors - even in a crowd or on a float - is at much lower risk, he said. Roy, who was not speaking on behalf of the university, said he plans to ride in King Arthur this year and typically does not wear a mask outdoors.

Exactly how comfortable an individual is with the various levels of risk ultimately comes down to one's own situation, and to health factors that can make them more at risk for serious disease, Roy said.

Infections will occur during Carnival, so parade-goers should choose their activities knowing that COVID is still present.

“Is it worth standing in a big crowd of people for five hours to watch three parades and catch the beads?” Hassig said. “The answer may be yes, but then you need to go into it recognizing that it is not without risk.”

The broader effect

On a broader scale, it's not clear exactly what effect Carnival will have on the pandemic's trajectory in the state.

"My sense is it's not going to lead to another spike just due to the timing, but a big caveat to that is I think we’ve all been humbled at every step of the way by this virus. So it's really hard to predict," said Kanter, of the state Health Department.

Health specialists urge more caution to prevent the most common injuries that send patients to the emergency room during Carnival: slipping on beads, alcohol-fueled accidents, eye and face injuries from throws, tripping over streetcar tracks and curbs and injuries from surging crowds trying to get the attention of float riders.

“I can’t tell you how many kids I’ve sent to the emergency room after parades from ladder accidents,” said Dr. Stephen Hales, founder of Hales Pediatrics and chair of Children’s Hospital.

And although parades and partying will likely trigger some infections, most health specialists agree the strain on the health care system is more immediately concerning. Health care workers are stretched thin after being pushed to their breaking point over the past two years, Hales said. The key to pulling off Carnival during COVID is balancing that with increased precautions.

“Do we worry about that? Yes. Do we stay home and lock the door? No, I don't think we do,” said Hales, who reigned as Rex, king of Carnival, in 2017. “What I'm hopeful we’ll do is we’ll celebrate, but we'll celebrate carefully enough that we don't add stress and strain to that.”