Nearly a decade ago, a fight inside a club along River Road in St. James Parish ended in the fatal stabbing of 25-year-old Christian Allen, his body left in the street outside the bar after his accused killer had fled.

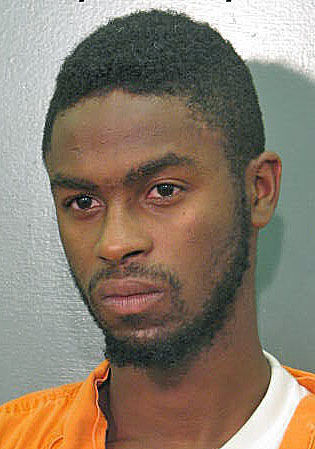

From early on, authorities had suspected Kyriene Vallery, then a 22-year-old who deputies say was seen fighting with Allen inside Club 7002 before the stabbing reportedly happened outside the bar.

After two previous trials for second-degree murder, both of which ended with guilty verdicts that were erased on appeal, prosecutors recently were able to negotiate a manslaughter conviction of Vallery. In the process, Vallery has gone from being sentenced to life in prison from his first conviction to one that amounts to a 15-year sentence with requirement to pay restitution of $20,000 to the Paulina man's family.

With the lesser sentence and the time that he has already served, Vallery's attorneys said they hope he could be out in less than a year.

Prosecutors in St. James didn't return an email, texts and calls for comment this past week.

The shifting fortunes of Vallery stem from the state's historic reevaluation of non-unanimous jury verdicts for serious, non-capital felony cases as triggered by a Louisiana constitutional amendment in 2018 and a significant U.S. Supreme Court ruling in 2020.

Only seen in Oregon also, Louisiana's former practice of allowing non-unanimous, or split, jury verdicts convict defendants was an unusual feature of state's judicial system with racist roots, legal experts have said.

The Louisiana constitutional amendment adopted on Nov. 6, 2018, however, did not apply to defendants like Vallery, who were accused of crimes committed before Jan. 1, 2019.

But, in 2020, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Ramos v. Louisiana that juries across the nation must be unanimous to convict or acquit a criminal defendant.

In the sweeping ruling, Justice Brett Kavanaugh's concurring opinion noted the practice was rooted in the retrenchment of Black civil rights in the Jim Crow South after the Civil War and Reconstruction. By allowing less than a unanimous vote to establish a conviction beyond a reasonable doubt, the practice undercut the voice of what usually was only a handful of Black jurors.

The ruling and others that followed cleared the way for state court defendants like Vallery to pursue new trials for older crimes, if their initial appeal rights were still alive.

Eric Santana, Vallery's defense attorney, said problems in his client's first trial forced a retrial, which, when the second verdict came back non-unanimous, had the inadvertent effect of keeping alive Vallery's right to pursue an appeal for a split verdict.

"He had redo if you will," Santana said.

Recording failures lead to second trial

A St. James Parish jury first convicted Vallery of second-degree murder in Allen's homicide in 2015, but District Judge Tess Stromberg of the 23rd Judicial District Court ordered a new trial in June 2017 after court officials discovered failures to audio-record some key testimony and bench conferences.

The breakdowns came to light after the trial ended. Under the law, the recordings are required, needed to create the formal record for a defendant's appeal.

Handed down just days before Louisiana voters would overwhelmingly decide to end non-unanimous verdicts, Vallery's second conviction for Allen's death came through a 10-2 verdict.

He was sentenced to 40 years in state prison months later in 2019, but, following Ramos, a state appellate court threw out that second verdict in late 2020.

Mark Plaisance, Vallery's appellate attorney, said Vallery gained a second, additional benefit under the new precedents that followed Ramos and the end of non-unanimous jury verdicts.

Once Vallery was able to challenge his second conviction over the split verdict, a helpful state Supreme Court precedent emerged from a high-profile, New Orleans-area road rage incident that killed Louisiana NFL running back Joe McKnight in 2016.

The Louisiana Supreme Court ruled in June 2022 that Ronald Gasser, the convicted road rage killer of McKnight, could not be tried again for second-degree murder because a 10-2 jury had convicted him of the lesser offense of manslaughter previously.

Gasser's manslaughter conviction was what's known as a responsive jury verdict, a lesser conviction that follows, under the law, if jurors don't find for the primary charge of second-degree murder.

Louisiana's high court found that Jefferson Parish jurors implicitly acquitted Gasser of second-degree murder when they convicted him of manslaughter, even though that conviction was a non-unanimous verdict.

The high court found prosecutors would violate 5th Amendment protections against double jeopardy had they attempted to try Gasser for second-degree murder again. Double jeopardy is the constitutional protection against being tried more than once for the same crime.

In Vallery's second trial, as happened for Gasser, divided jurors convicted Vallery of the lesser charge of manslaughter, passing over a second-degree murder conviction.

After many years, a quick end

Before the 2022 Supreme Court ruling came down, however, prosecutors in St. James had already begun initiating steps for a third second-degree murder trial.

Santana, Vallery's defense attorney, objected on double jeopardy grounds then, but Judge Stromberg rejected them in late 2021, only to have the state Supreme Court go the other way for Gasser in the McKnight case months later.

Citing that high court precedent, a state appellate panel found similarly for Vallery in October 2022. Faced with trying to prosecute Vallery a third time on the lesser manslaughter charge, prosecutors in St. James negotiated a plea this month.

Plaisance, Vallery's appellate attorney, said Allen's slaying involved witnesses who saw what happened as a fight between two former friends, leaving inconsistent testimony at trial.

Though prosecutors pursued second-degree murder charges, Plaisance said, he believed the proper charge had always been manslaughter.

"As you can tell, now that it got dropped to manslaughter by … the court rulings that have occurred (out of Ramos), it seemed to get resolved much quicker than if it would have continued on as a second-degree murder case," he said.

Under the deal, Vallery, 32, admitted on May 10 in Convent that he had killed Allen on Nov. 28, 2013, and pleaded guilty to manslaughter, according to court papers.

Under the agreement, Judge Stromberg gave Vallery 25 years in prison but suspended 10 years. He also must serve 10 years of probation after he gets out, according to court papers.

Under the sentence, Vallery had to pay $10,000 to Allen's family at the time of the conviction, with the remainder to come once he gets out, possibly in eight to nine months.