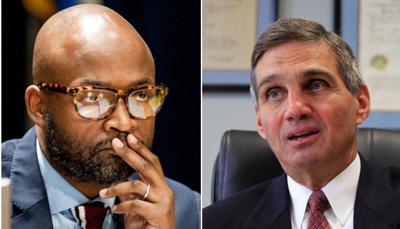

The wheel came full circle a couple of weeks ago when New Orleans District Attorney Jason Williams took Emily Maw to task for refusing charges against 15 men accused of bearing illicit arms along Mardi Gras parade routes.

Maw, former head of the Innocence Project in New Orleans, was a major player in Williams' election campaign, which prevailed with pledges to give New Orleans a gentler, kinder breed of prosecutor. Williams, as a former criminal defense attorney, had extensive contacts in the ranks of the bleeding hearts, and he put several of them on the public payroll when he decided to wear a prosecutor's hat. Maw was prominent among them.

Williams put her in charge of a civil rights division, a novel concept in an office plagued for years by accusations of constitutional violations. One of her main duties was righting injustices wrought under former district attorneys, including Williams' immediate predecessor Leon Cannizzaro.

Cannizzaro was a prosecutor of the old school, who believed his job was to make sure that criminals spent as much time behind bars as possible. He had bad kids tried in adult court, where they faced longer sentences, and wheeled out habitual offender laws to get criminal court's regular customers sent up the river for more years than they were likely to live. Cannizzaro applied frequent offender laws more often than any other Louisiana district attorney and had no time for judges who displayed namby-pamby tendencies.

Maw and Williams had an especially long list of ancient miscarriages to correct, since Louisiana was one of only to two states that did not insist on unanimous verdicts until the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in 2020 that the Constitution required them. The decision was not retroactive, but Williams ordered a review of long-forgotten cases anyway.

When Williams took office, he was not alone in doubting the wisdom of heavy-handed police tactics and draconian punishment. Indeed, a mildly reformist mood briefly seemed to be sweeping the country, but nowhere was the contrast more marked than in New Orleans when Williams took over, promising to dismantle pretty much the entire Cannizzaro legacy. Henceforth, for instance, juveniles would remain in juvenile court and assistant district attorneys would not be looking to lock up offenders until Kingdom Come.

As the murder capital of the U.S.A., New Orleans had no obvious incentive to give criminals a break, and such idiotic slogans as “defund the police” soon brought the reformist cause into national disrepute in any case. The movement that enabled Williams to oust that alleged mossback, Cannizzaro, was therefore on the way to being hopelessly outdated by the time the election returns were in. That's when Williams commenced his systematic reversal of just about every policy implemented when Cannizzaro was king.

Williams has since evidently decided that, in this crime-ridden city, Cannizzaro was right all along, and has reinstituted, on rare occasions, multiple bills and adult charges for juveniles.

Cannizzaro did not seek reelection, having been overtaken by the desire to spend more time with family that often overtakes politicians with fat pension rights faced with a tough campaign. They can't be blamed for that; it's the smart thing to do.

So far as the voters are concerned, however, the election looked very much like a confidence trick. We voted for Williams as the antithesis of everything Cannizzaro stood for, but the Williams we elected has now emerged as the old Cannizzaro redux.

Email James Gill at gill504nola@gmail.com.